Big Ears founder Ashley Capps on the art of collaborative curation

The master promoter tells the story of his one-of-a-kind experimental music festival.

Ashley Capps, photo courtesy of Big Ears.

Ashley Capps, photo courtesy of Big Ears.

You won’t find many festival promoters like Ashley Capps. A Knoxville native, he built AC Entertainment into a music empire centered in his unassuming Eastern Tennessee hometown. It all started with Ella Guru’s, a 220-capacity club (often pushed past 250 on busy nights) in the once-deserted, now-thriving “Old City.” From the Neville Brothers, who played the venue’s opening night in 1988, to the Goo Goo Dolls, who performed its final show a week before Christmas 1990, Ella’s was a proving ground where Capps learned the ropes of concert promotion and experimented with ambitious bookings — Emmylou Harris, Townes Van Zandt, and Garth Brooks, but also jazz greats like Wynton Marsalis, Tony Williams, and Jay McShann, and African giants King Sunny Ade, Baaba Maal, and the Bhundu Boys.

These bookings would have made perfect sense in New York or L.A., but bringing some of those artists to Knoxville was risky; touring costs money, and tickets need to sell. Nearly 20 years later, Capps applied the same forward-thinking attitude to the founding of Big Ears Festival, which held its 10th iteration (spread out over 15 years) on the final weekend of March.

“Knoxville is, in many ways, our secret weapon,” Capps told me over the phone before this year’s festival. It’s true that Knoxville is an asset to the festival — not, as New York noise heads might assume, a setback. Running from show to show between the historic theaters on Gay Street, the churches and cathedrals on side streets downtown, and the Old City’s motley group of clubs and performing arts spaces, is half the fun. But the main draw to Big Ears, bringing thousands of experimental music enthusiasts from across the country to a city that’s surprisingly expensive to fly to, is its sprawling, creative programming, almost all of which is handled by Capps himself. Where most contemporary festival promoters — especially those operating at the behest of the few mega-conglomerates that have monopolized the industry — triangulate their lineups around an imagined audience archetype, defaulting to the lowest common denominator, Capps curates based on his expansive personal taste, and that of a few trusted peers. In so doing, he’s created a festival unlike any other, with all the quirks and surprises of a veteran music lover’s record collection.

John Zorn performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Cora Wagoner, courtesy of Big Ears.

John Zorn performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Cora Wagoner, courtesy of Big Ears.

One of those trusted peers is experimental music and DIY legend John Zorn, who’s been talking to Capps about joining the Big Ears lineup for over a decade. He finally came in 2022, not only performing but also programming and conducting a number of his own compositions, taking over the historic Bijou Theater for hours at a time. This year, in celebration of his 70th birthday, he stepped up to do the same at the much more cavernous Tennessee Theatre, recruiting today’s musical avant garde — Mary Halvorson, Simon Hanes, Julian Lage — to play alongside icons like Bill Frissell, Marc Ribot, and John Medeski. He closed out Big Ears 2023, leading a lively performance of his beloved “game piece” Cobra.

“Big Ears is the most diverse, open-minded, and expansive music festival in the country,” the notoriously press-shy Zorn told me over email. “Their entire team exhibits an attention to detail that is inspiring. You truly feel that they appreciate your work — and most importantly they treat every artist with total respect and love… This special generosity of course comes directly from… Ashley Capps. His positive spirit and glowing enthusiasm for music of all shapes and forms can be found in every member of his team. He has a profound knowledge of music and also retains a youthful enthusiasm that inspires you to do your very best. He also exhibits a daring and courage in presenting cutting edge work by young musicians that is quite special. His motivations are not money and fame — his motivations are in presenting great and expansive music — and therein lies our common ground.”

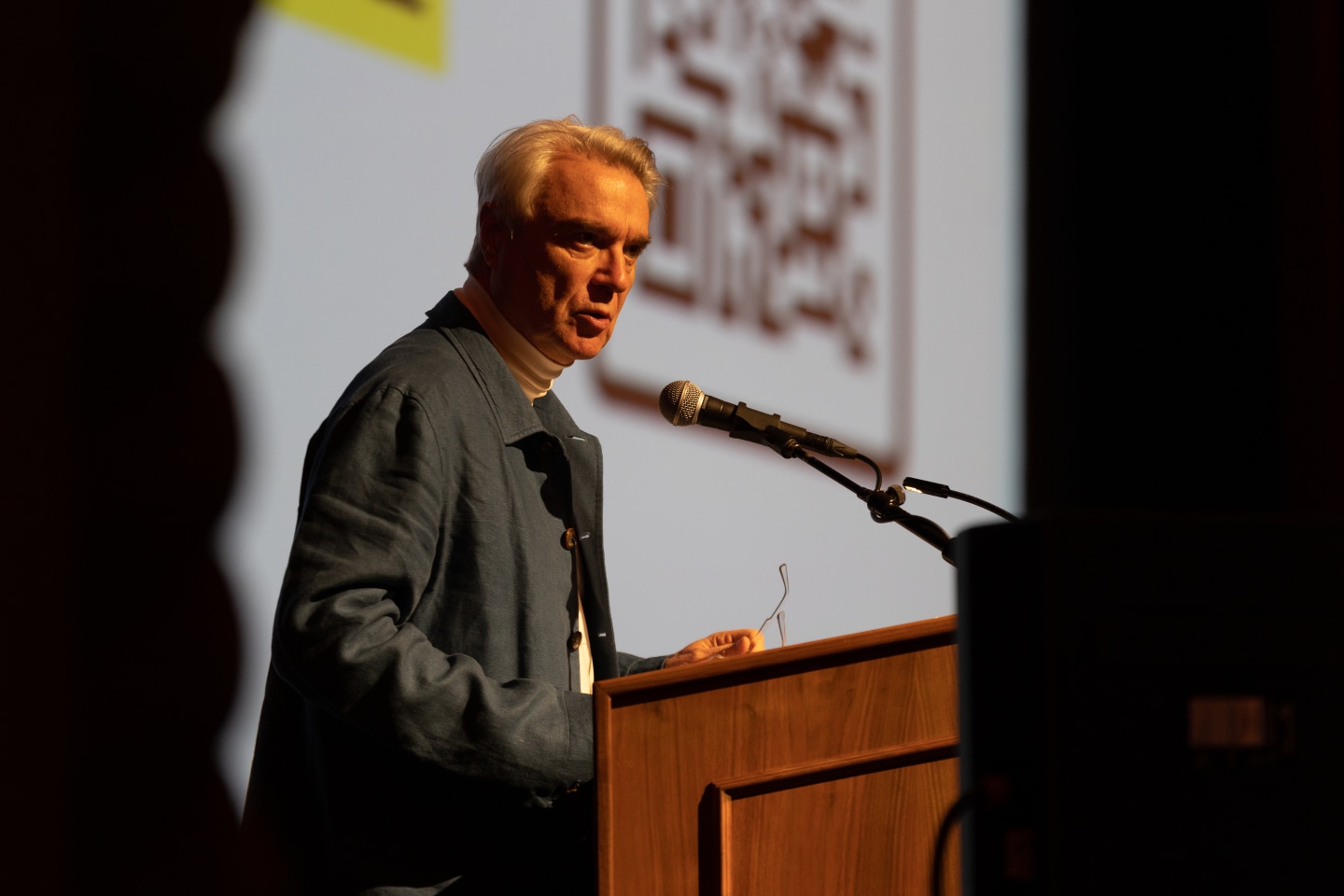

David Byrne speaks at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Cora Wagoner, courtesy of Big Ears.

David Byrne speaks at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Cora Wagoner, courtesy of Big Ears.

Lily Keber — the celebrated music documentarian who helped rebuild Big Ears’ defunct film program this year along with the Haitian-New Orleanian interdisciplinary artist and curator Nic[o] Brierre Aziz — gave Capps’ collaborative spirit a similarly glowing review. “It speaks to Ashley’s character and artistic vision that as soon as I asked if I could help out… he jumped on it and said that he would love to have my contributions — and then, after that, left it completely open to wherever I would like to take the film curation,” she said. “I checked in with him about some things, but I got the sense that I didn’t even need to — that he was down to just see what I would bring to the film program. It felt really exciting and very fun to be in that creative space of, ‘Let’s find what a film program at a festival like Big Ears even means.’”

What it meant this year was a carefully selected array of films and discussions that included everything from an experimental Appalachian 16mm short with live musical accompaniment to the films of David Byrne, who was essentially Keber and Aziz’s analog to Capps’ Zorn, contributing a sizeable chunk of the festival’s programming with his own impressive body of work. Another highlight was a panel on film scoring featuring Son Lux, who provided the soundtrack to 2023’s Best Picture winner, Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Whomever Capps is working with — whether it’s a flexible filmmaker like Keber or a stubborn, late-career legend like Zorn with a singular, uncompromising vision — Capps seems content to let others take the reins, so long as he trusts them and respects their work. (“I do not accept a gig unless I have this kind of freedom and latitude,” Zorn stipulated. “For me, it is always a matter of a personal connection with an individual that makes these events happen.”)

Speaking to Capps, his generous spirit was immediately evident. He gave me more than an hour of his time two weeks before the start of Big Ears, and answered all my questions with deep consideration — even the uncomfortable ones. We talked about Knoxville’s advantages as a festival host, collaboration in curation, and the obligation progressive artists and promoters have to push back against unjust legislation like Tennessee’s new drag ban. We also touched briefly on another festival Capps helped found: Bonnaroo.

Ashley Capps, photo courtesy of Big Ears.

Ashley Capps, photo courtesy of Big Ears.

Big Ears is obviously a different sort of festival than Bonnaroo. It doesn’t have a ton of corporate sponsors, and its headliners often don’t have a huge amount of crossover appeal. The lineup this year seems strikingly democratic — the poster, even, is alphabetical. What inspired you to build something so strikingly different (and so much less profitable)?

Big Ears started very small in 2009, and very organically. It had been discussed for a number of years and was rooted in a passion for music that wasn’t always on people’s radar screens, that had much more niche audiences. As a promoter, I wanted to see if we could build larger audiences for some of that music and put it in a context where it could be heard by more people who might have been somewhat unaware of it but would appreciate it if they had the chance to hear it.

But it was inspired by many things. I remember being at a DJ Shadow concert and hearing this amazing piece where he samples Meredith Monk. And I knew that bands like Radiohead and The National were inspired by Steve Reich and Philip Glass and all these other influences that you could hear creeping into their music. The music that those bands make is distinctive and unique in its own right, but those influences aren’t always apparent. So it struck me as an interesting idea to explore those musical tangents of “this leads to this leads to this.”

It’s not that unique of an idea. I see a lot of parallels between the programming ethos of Bonnaroo, especially in the early days, and the way Big Ears is approached. We would have The String Cheese Incident, for instance, and then think, “Well, we should have Bela Fleck.” And then it’s like, “Well, what about the Del McCoury Band?” You go deeper and deeper.

One of the great strengths of working with so many jam bands is that they’re deeply influenced by so many different types of music. So we were able to venture into jazz and African music and different kinds of folk and program those in the festival too. That voyage of discovery is really at the heart and soul of [what we do].

The main difference with Big Ears is we don’t have the huge headliners, but we have more headliners than ever. Over the years we’ve had Wilco. This year we’ve got Andrew Bird. We’ve had Patti Smith, and so on. We’re not averse to headliners. But the parameters are dictated by a different aesthetic: the intimacy of the venues.

Lonnie Holley performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler and Dave Eggar, courtesy of Big Ears.

Lonnie Holley performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler and Dave Eggar, courtesy of Big Ears.

The interactivity with the city is another thing that makes Big Ears feel special. There are other festivals that do that, but I’ve never been to one that does it to the same extent, where you’re running around a downtown area from show to show all day and night. It’s really fun.

I’m glad to hear that because, when we first launched Big Ears, there was a surprisingly negative reaction to the fact that it was in Knoxville. Part of that was because the music was perceived as being cutting edge and progressive, and why would you be doing that in Knoxville, Tennessee? But Knoxville is, in many ways, our secret weapon. We have some incredible venues. They’re all within walking distance of each other. Knoxville’s maintained its historic character, so it’s a nice place to hang out. And it enables — because the downtown footprint is relatively small and people can walk to all of the venues — a certain interactivity amongst the audience and often with the artists.

It also supports the shared experience of people coming together for a common purpose, which is at the heart of any festival. Usually that’s because everybody’s together in a field, but that’s much more difficult to replicate in a city. So the size of Knoxville and the good fortune of having these great venues that are all so close to one another has been a key ingredient to the festival’s success.

Big Ears’ lineups have become much more sprawling through the years, but they’re still full of surprises. Are you still pretty much in charge of the curation?

I am the curation of Big Ears — primarily, at this particular point. At various points, I’ve had collaborators and partners in some of the programming, and I love collaborating. So while I say that I’m the curator, I’m always looking for ideas and talking with artists and my peers and friends in the industry. It’s an ongoing process, and I’m constantly stealing ideas from all of the conversations I have and from the experiences I have going to see music myself. Ultimately, I’m the decider, but it’s a very open, collaborative experience.

FUJI|||||||||||TA performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler, courtesy of Big Ears.

FUJI|||||||||||TA performs at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler, courtesy of Big Ears.

Speaking of collaboration in curation, John Zorn has curated a solid chunk of the Big Ears lineup these past two years. Tell me about your relationship with him, and about the programming for his 70th birthday celebration this year.

He and I have talked about the festival going back many, many years. I first saw John in concert around 1980 in New York, and I’ve seen him many, many times over the years. I brought him to Knoxville with the original Masada back in the mid ’90s, so we’ve had an ongoing dialogue about him appearing at the festival. His aesthetic is completely aligned with that of the festival, so it’s surprising that it took as long as it did. When it finally came to fruition in 2022, we had no idea we’d do the 70th birthday concerts in 2023. But I think the response blew John away. That’s the way things evolve in the programming. This time last year, it was just an idea.

Big Ears has been an incubator for some pretty special collaborations between artists, and I’m sure some powerful, lasting relationships have been forged through these spontaneous partnerships. Do any of these moments from festivals past stand out to you?

These are the kind of questions that people ask me and suddenly my mind goes blank. I know there are many, but I’d have to think about it for a minute. Sometimes the collaborations have their roots outside the festival, so by the time they get to the festival, it’s already an evolving process. Joe Henry bringing Jason Moran and Marc Ribot into his band last year was a special moment. We had Shodekeh Talifero, the human beatbox, last year. And from his appearance here, he scored a film called King Coal that just premiered at Sundance, made by a documentary filmmaker who lives here in Knoxville and teaches at the University of Tennessee. Now that I’m thinking about it, there’s tons of stuff.

There’s an ongoing series of collaborations that emerge during the festival but sometimes don’t come to fruition until later festivals, or projects that take place outside of the festival. My curation doesn’t extend to pushing collaborations. My goal as a curator is to create situations where things emerge naturally. I know artists are having conversations, and some special things may emerge from that, but I won’t be sure until they actually happen.

Sam Wilkes (left) and Sam Gendel perform at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler, courtesy of Big Ears.

Sam Wilkes (left) and Sam Gendel perform at Big Ears 2023. Photo by Billie Wheeler, courtesy of Big Ears.

If you could draw a throughline between the great performances at Big Ears over the years, is there a secret ingredient? For instance, is an element of transgression necessary?

I wouldn’t say so much transgression as transcendence, where an artist is so fully inhabiting the musical world they create that it becomes an all-consuming experience for everyone who’s there. That, to me, is the heart and soul of Big Ears. It’s not the transgression; it’s the transcendence.

Big Ears is happening as the Tennessee drag ban goes into effect. Bonnaroo put out a statement saying there wouldn’t be any changes to the program. I know you’re not involved with that festival anymore, but does Big Ears have a similar response?

We’re definitely not making any changes to programming either. We don’t have any drag performances per se planned. Technically speaking, the law bans drag performances that are sexually explicit or obscene from happening in front of children. You can make the argument, accurately, that obscene, sexually explicit performances are already banned in front of children. So it’s at best unnecessary and at worst deliberately provocative, because it targets a certain group of people in a certain type of activity. But it doesn’t technically ban drag.

It’ll be interesting to see how the law is actually enforced. But obviously — I hope it’s obvious — Big Ears is rooted in the ethos of freedom of expression for all. The whole festival is about bringing communities together, including communities that don’t always spend a lot of time together. It’s about opening up conversations between those communities. The freedom to explore ideas and to explore the creative process, that’s at the heart and soul of who we are. Obviously, a ban on drag performance is completely contrary to that aesthetic.

I know you can’t say, “Performers at our festival should break the law.” But do you think festivals like Big Ears that are so fundamentally opposed to the restriction of personal expression have a duty to protest these laws in some way?

There’s a lot going on in the political spectrum that concerns us, and much of it is deeply the antithesis of everything we stand for — whether it’s book banning or not teaching certain subjects or perspectives in schools. All of that is completely contrary to our aesthetic. Embracing the diversity of what it means to be human and all the manifestations of that… It’s who we are. So yes, we are fundamentally opposed to anything that tries to demonize that.

I think Big Ears’ ethos speaks for itself. I can’t think of any arts organization — in the southeastern U.S., especially — that has booked more gay, trans, LBGT performers, as well as Black performers, Asian performers… The balance of female and male performers is very strong. But we’ve never booked anything because an artist is any of those things. We’re trying to present the world’s greatest performers and the most powerful, influential, exciting, groundbreaking musical performances we’re aware of. And whether those performers are from the LGBT community or from whatever country throughout the world, that’s always a secondary concern. It’s the quality of the performance that’s first and foremost in our minds.