Earl Sweatshirt: Bless This Mess

Earl Sweatshirt comes home.

From the magazine: ISSUE 85: April/May 2013

Earl Sweatshirt’s apartment is a nightmare—four laundry baskets, seven video game controllers, Budweiser empties, potato chip shrapnel, blunt guts, skateboards and dust bunny warrens galore. There’s a paper towel magneted to the fridge that says “Fuck You!” scrawled in Sharpie. The walls may be marked with dingy fingerprints, but Earl’s starter apartment is one of a specific mien; he lives in the same complex Bay Area YouTube rapper Kreayshawn moved to when she signed her purported $1 million deal with Sony. Last year, Earl signed his own papers with Sony, securing an imprint called Tan Cressida with distribution through Columbia. He likes the digs but loves the complimentary Flavia coffee machine in the leasing office. “I’m hyped on it,” he says. “I drink that shit every day.”

Earl Sweatshirt is a rail-thin kid with a big mouth, arched eyebrows and a shadow of a mustache. He has a faux black leather couch, a massive TV and a sink full of dirty cups—just cups—and in tandem, these cues serve to remind you that the 19-year-old rapper born Thebe Neruda Kgositsile is a kid. Wearing a Supreme hat, his baby face belied by eyebags, he holds for a deadpan high five at his front door and turns around to smoke a cigarette out the back. It’s shortly after 1:00PM and he’s just woken up. “You don’t want to sit there,” he says, motioning to an enormous black bean bag. He’s right. It’s lousy with carpet hair.

Earl came up as a member of the Los Angeles-based rap collective, Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All, which rose to internet infamy in 2010. The clan’s numbers vary from 20-something to 60 depending on whom you ask, the most visible members being the irascible polymath rapper Tyler, The Creator, and R&B outlier Frank Ocean. In May of 2010, the then 16-year-old Earl Sweatshirt released the video for “Earl,” the title cut of his 10-track eponymous mixtape. The lyrics are heinous, chronicling kidnapping, rape, murder and cannibalism. The video features Odd Future members marauding, skating, and bleeding out from ODing on a putrid drug cocktail. Teeth are dislodged, as is a fingernail, and the footage, which includes nipple hemorrhaging, has been viewed over 12 million times on YouTube. “Talking about outlandish shit had become a competition between me and Tyler,” Earl tells me, packing a joint with the aglet of his shoelace while sipping on a Budweiser. “We were so fucking cocky.” The mixtape as a whole boasted such vivid storytelling and startling linguistic agility that fans drew comparisons to Eminem, with one crucial distinction: Odd Future had the internet. The combined fervor on YouTube, Tumblr and Twitter established the L.A. crew as a marketing juggernaut. Earl Sweatshirt, the runty kid with the outsized brain, looked like an underdog but felt like a sure thing.

By the end of 2010, Earl had earned its rightful place among early-adopter music sites’ “Best Of” lists—as did Tyler’s album, Bastard, despite dropping in late 2009. Odd Future’s mixtape, Radical, was released the same May as the “Earl” video and only served to galvanize the crew’s cult following. It looked like the ragtag family was having a blast. And then somewhere in the fray, like a patsy in his own songs, Earl Sweatshirt went missing.

“Free Earl” became a rallying cry amongst Odd Future members and their rapidly multiplying followers. His absence would last two full years and it would later come to light that his mother, Cheryl Harris, a professor and lawyer, had shipped him off to reform school overseas. On April 14th 2011, Complex magazine discovered a student by the name of Thebe Neruda Kgositsile attending Coral Reef Academy, a military school in Polynesia. A month later, an eight-thousand word article in The New Yorker written by Kelefa Sanneh confirmed Earl’s whereabouts with official word from his mother and his estranged father, the South African poet laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile. Earl became a celebrity in absentia, a profoundly new phenomenon and a strange byproduct of Internet fame. There were “Fuck Earl’s Mom” chants at shows and even threats. In support of his mother and in defiance of every convention in rap, Earl asked to be left alone. “The only thing I need as of right now is space,” he said to The New Yorker in an email. “I’ve still got work to do and don’t need the additional stress of fearing for my family’s physical well-being. Space means no more ‘Free Earl.’”

Samoa, meanwhile, was rough. “You cleaned a lot,” Earl says, a year after his return. “You had therapy two or three times a day, and you’re with the same fucking 20 dumb-asses who are just like you. Every day. There were the behavioral kids and the drug kids. I was both.” The experience was designed to be isolating: “You’re not allowed to have contact with none of your homies. No Facebook. No internet.” But Earl did everything he could to keep up with his friends’ thriving careers. “It was some conniving shit,” he says. “I read Hacking For Dummies and set up a keylogger to get the administrative password to get onto the internet. I’d log onto the Odd Future Tumblr and leave shit in drafts and then Tyler would write me back.” These days, Earl smokes cigarettes and a fair amount of weed, but little else. He’s also simultaneously on his phone and laptop for most of his waking hours. Samoa may not have been a cure-all for Earl’s hard-bitten habits, but emotionally, his outlook has improved. “Things used to be dark and weird,” he says.

Shortly before his 18th birthday, Earl graduated from reform school to finish the rest of senior year in LA, a prospect fraught with anxiety. “My friends were on eggshells, I’d get nervous and my palms would get sweaty,” he says. “Not only was I coming back to Los Angeles, I was coming back to Odd Future Los Angeles.” He was recognized at LAX arrivals by a police officer who looked him dead in the face and said, “Earl Sweatshirt.”

Today, Earl is cautious when discussing the frenzy his absence created. “I’m not gonna lie and say that whole shit hasn’t changed my relationship with my fans,” he says. “People being that pissed off at my mom—it hit really hard.” Before being sent away, Earl had been acting out at home and in school. “I didn’t have a dad coming up,” he says. “I didn’t have someone to be scared of.”

Earl saw his dad, upon his return from Samoa, but is not wordy on the experience. “It was crazy,” he says. In the New Yorker article, when Earl’s father was asked whether or not he was familiar with his son’s work, he said he was not. The poet was disinclined to pry, reasoning that when Earl was ready to share music with him, he would. Earl finds reassurance in his father’s response. “I fucked with him after that,” he says, punching a palm for emphasis. “I would’ve been sad as fuck because I actually would’ve never talked to that nigga again. I’m so glad my dad’s not thirsty.” Earl gets up abruptly from the couch to find a lighter, a quest he embarks on several times over the course of the day. He gives up and lights the joint on the stove, changing the subject from his dad to his debut album, Doris, slated for a May release and named after his late grandmother.

Earl is anxious to release new material. His absence and the dearth of songs led to the unearthing of a mixtape he made under his previous moniker, Sly Tendencies, a discovery that embarrasses him. “That was never supposed to come out,” he says. “I recorded it in my room and you can hear the third-grade basketball medals hitting my computer.” The first single from Doris, “Chum,” was released this past November. It has somber lyrics, and the video’s set in black-and-white, featuring Earl staring straight ahead. Losing the creaky, pre-pubescent timber of his youth, Earl’s voice is considerably deeper, authoritative. “Chum” doesn’t glitter with inchoate glee at notional ultra-violence like “Earl” does. In fact, the lyrics are in large part about his dad: It’s probably been 12 years since my father left, left me fatherless/ And I used to say I hate him in dishonest jest. The song is revealing, a fair vantage from which to lambaste those who intruded on his privacy two years ago: Craven and these Complex fuck niggas done track me down/ Just to be the guys that did it, like, I like attention/ Not the type where niggas tryna get a raise at my expense/ Supposed to be grateful, right, like, Thanks so much, you made my life harder and the ties between my mom and I are strained and tightened. He reinforces that he’s a real kid with a traumatized family, and not the prize to an elaborate scavenger hunt of the internet’s making.

Doris is a different story and Earl is aware of the pressure. “The anticipation scares the shit out of me,” he says, squinting against the smoke of a cigarette. In its one-two-punch roll-out, the next drop is the Tyler-directed video for Earl’s second single “Whoa.” It’s way less serious than “Chum”, in fact, it’s an Odd Future anthem—the refrain is the spelled-out spoonerism for Wolf Gang. Earl’s lyrics are effervescent and flip. “Set them nettled critics to the bezzle stop, dead and wrong/ Get ‘em higher than the pitch of metal tea kettle songs.” It’s a cheeky hat-tip to The New Yorker article that cites Odd Future’s “willfully repugnant lyrics” as “designed to nettle cosmopolitan listeners.”

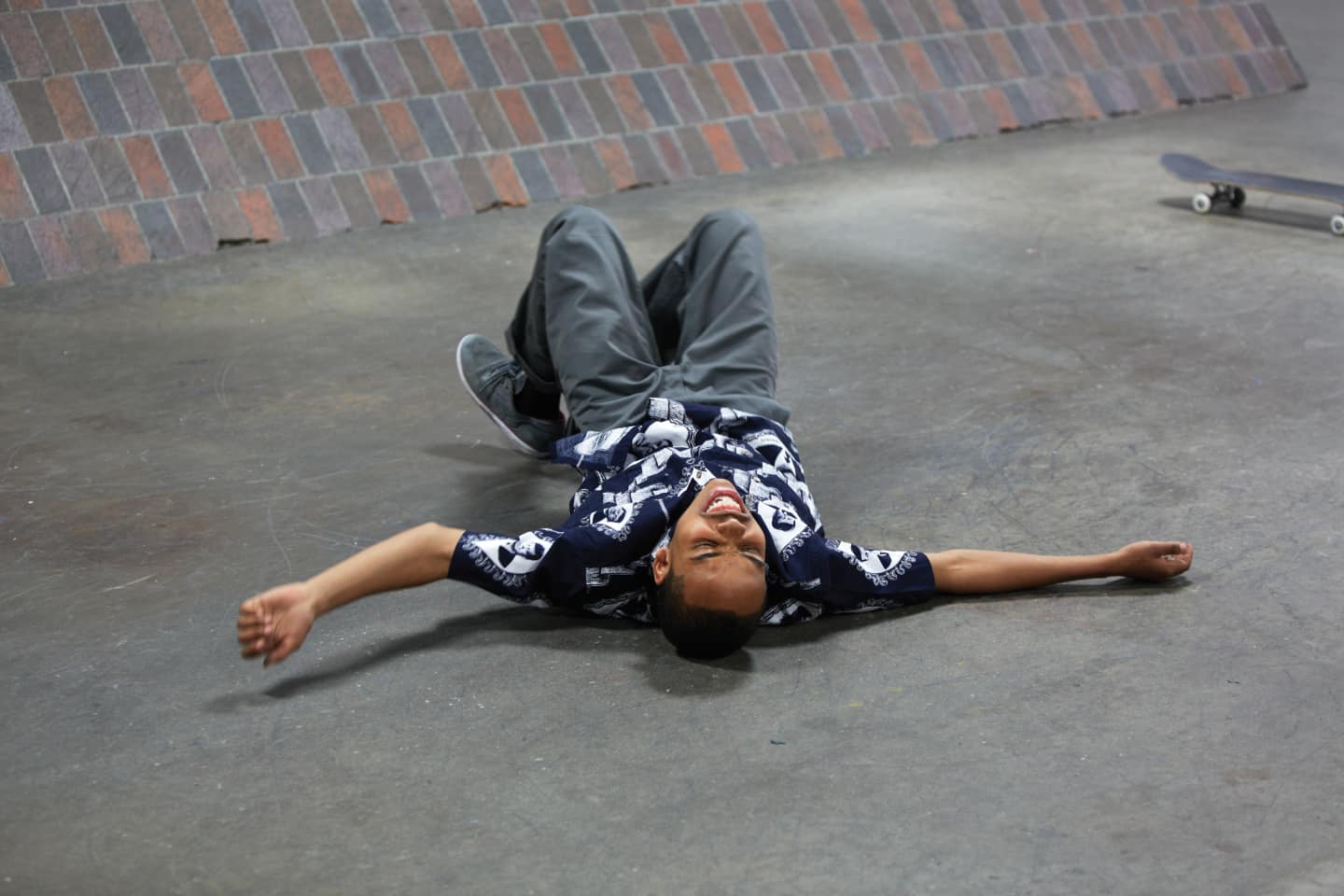

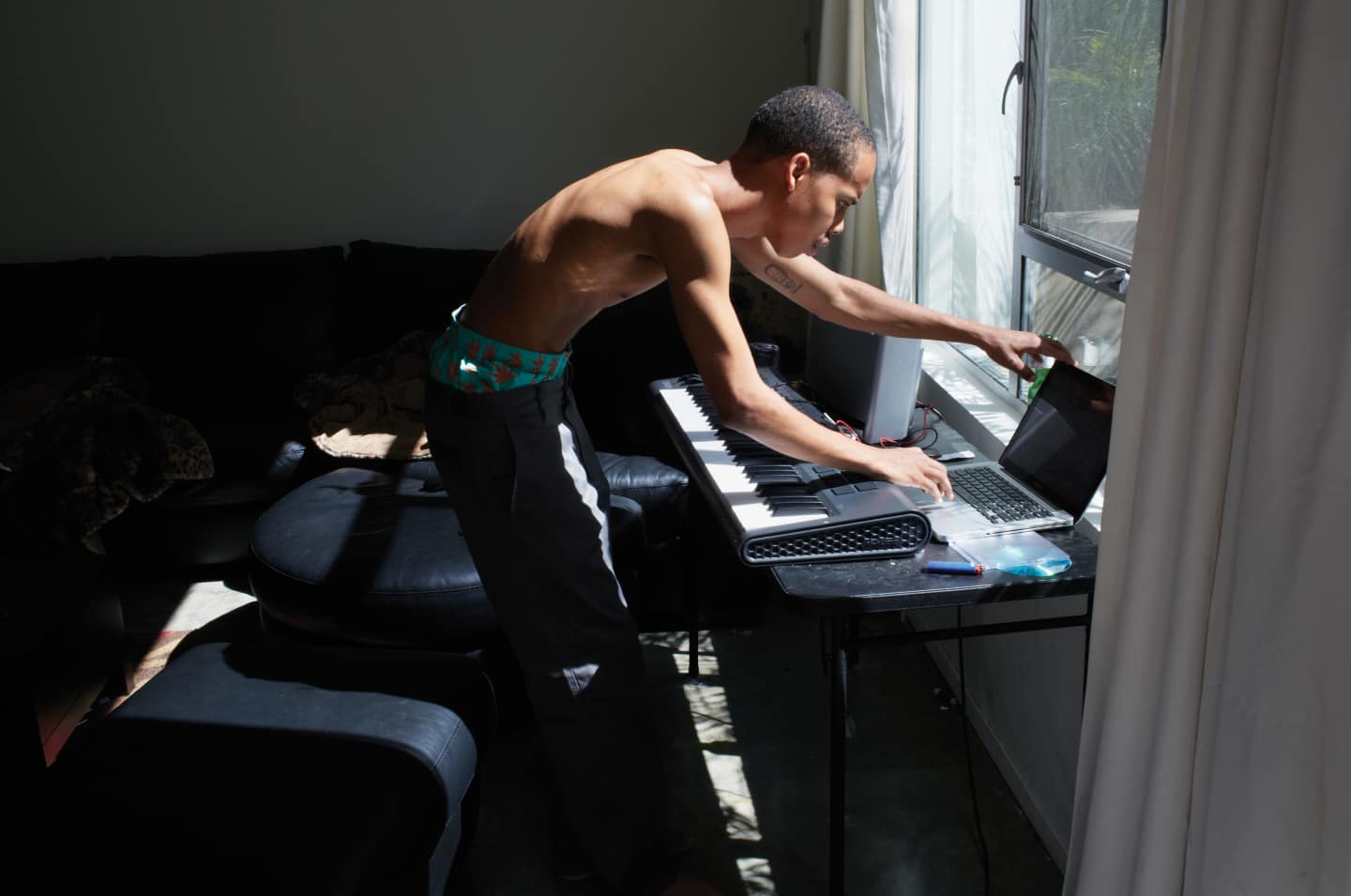

Earl is an exceptional lyricist and more recently, a capable producer. He makes beats under the sobriquet RandomBlackDude and credits his Samoan sojourn with the decision to learn when he got back. “It was a confidence thing,” he says. He made one two days ago at his apartment, on Logic, on a laptop set up on a folding plastic card table. He listens to it constantly. The gestating track is referred to as “Fookie.” Until a song is complete, it carries a bullshit name that’s the first thing that Earl thinks of when he hears it. The melody is blue and the tempo unhurried. There’s distorted electric guitar, wobbly keyboard chords and snare drums that add an antsy military-funeral vibe. This song will likely be the finale on the album. “There was a moment a month ago when I was mentally 100 percent finished with the record,” he says. “I just wanted it out, like, hurry up.” A bum hard drive corrupted the sole copy of a different track, and Earl elected to scrap it instead of salvaging it. “It’s not evolving,” he says of the album. “It’s writhing on the floor, and I’m in the house looking for something to bludgeon it.”

Completing “Fookie” is a priority with the album’s delivery date nearing, and to do that Earl needs studio time. On the poured-concrete back patio of Earl’s apartment, the rapper gets on the phone while pulling on a Camel. Wiry, college-aged kids in mirrored shades and microscopic swimsuits walk by towards the pool. Earl calls Mac Miller, the Pittsburgh rapper whose debut Blue Slide Park, topped the Billboard 200 album charts in late 2011. The two met through friends and work together frequently. “Scary Movie 5?” Earl says into the phone, laughing. “I don’t know if that’s cool.” Apparently, there’s a scheduling conflict, because Earl wanted to record at Mac’s, but Mac is filming a lampoon horror scene with Snoop Lion. You can hear Mac’s laughter through the phone. They agree to meet in an hour, and Earl offers to bring food.

Miller’s digs are considerably flashier than Earl’s. A stark, white Entourage McMansion in the Hollywood Hills, it features a pool, two recording studios and an automated gate. It can be seen with some frequency on MTV2 as a part of Mac’s reality television show which he jokingly drags into conversation every chance he gets. Miller meets us at the foot of his driveway, bows deeply as he introduces himself as Malcolm and then immediately backs into a parked car on the walk up.

The studio Earl uses is Mac’s converted pool house. It’s ensconced in ambient red light and features a gigantic Buddha head. There’s a large keyboard, a wall-mounted flatscreen TV and professional studio monitors. According to Forbes, Mac made $6.5 million last year. He released five mix tapes before his first studio album while grappling with a promethazine addiction that he’s since kicked. The trajectory makes you wonder what might have happened had Earl stayed his course—whether or not he would be a millionaire, if he’d have squandered his spoils succumbing to escalated drug use, or if by now he’d be a colorless rapper with a flabby viewpoint and nothing to prove. It also reminds you that despite Samoa, Earl is still young enough to be corruptible. There’s a moment when Earl and Mac rap silly jokes to each other in a huddle, whispering gleefully, and they look like college kids cutting class. They plow through styrofoam containers of Korean-Hawaiian grilled chicken and watch a rerun of Tyler’s recent appearance on Fallon, debuting “Treehome95.” Tyler’s grinning, sunglassed face moves across the screen from behind a shiny black piano that he plays beautifully. “We’ve been waiting so long for America to see this,” Earl says. “To see his appeal. Tyler’s so good I hate it.”

Mac and Earl get spectacularly high and listen to a song they recorded together called “Guild.” It’s a murky, slowed-down track that Earl loves because they both sound mean and not at all like themselves. They trade verses, volley cadence shifts, and the song is suffused with classic rap bragging. Mac: Moms love me cause I’m so commercial/ Fuck ’em raw cause I know they fertile/ Myrtle Beach with a purple fleece/ Hotel lobbies playing “Für Elise”/ I’m Ron Burgundy mixed with Hercules. And Earl: Tell the label that I want a white driver. After Mac leaves to shoot his Scary Movie scene, Earl records a verse for “Fookie” with DJ Money, Mac’s sometime DJ and an occasional producer. Money is also high, wearing a wife beater and socks with flip-flops. “Fookie” is seemingly addressed to his girlfriend, who lives in New York: I just hope that you listen/ And if I hurt you I’m sorry/ The music makes me dismissive… Later in the song, he gets a little more specific. I could be misbehaving, I just hang with my niggas/ I’m fucking famous if you’ve forgot/ And I’m faithful despite all what’s on my face and in my pockets/ This is painfully honest and when I say it I vomit .

“Fookie” is frank, and there’s a confidence in the economy of his prose. “Saying clever shit very plainly is the best,” he says, though it’s not a skill that comes naturally to Earl. “A lot of times, I write and have to scrap it. You don’t know what I’m talking about because the words are too much and it’s overwhelming.” Doris is similarly distilled. There are scant gimmicks—no club bangers, few singsong hooks with predictable radio appeal. There is a notable feature by RZA, cut up from an eight-minute freestyle, and beats by Pharrell and The Alchemist. It is thoughtful, reflective and brave for its vulnerability. There’s a thorough lack of easy shock.

In essence, it’s a rap album that a 14-year-old Earl would have been blown away by and that a 16-year-old Earl would not have been able to make. Earl says “Fookie” will be among the songs he’s sure he’ll show his dad. It took three years to conceive and an hour to write. Back at his apartment, he listens to the latest version, happy that he lightened the organs at the end. “Before, I didn’t have a strong sense of identity,” he says, sinking into his couch to roll another joint. “If I hadn’t left, my album would’ve sounded cool but it would have been useless.” He checks his pockets for a lighter that isn’t there. “I’m finally saying some shit.”