Buy a print copy of the Rema issue of The FADER, and order a poster of his cover here.

I first meet the 19-year-old wunderkind born Divine Ikubor — Rema, to his growing legion of fans — at New York City’s Hayden Planetarium right after Halloween weekend. Despite the weather being moderately warm for a November morning, he’s donning a black lightweight shearling jacket with his arms tucked into his torso area. He stands about 5’10’ in height with an athletic build; though he’s nearing 20, his face, devoid of facial hair, suggests that he could be as young as 15.

Rema just got in town less than a day ago after a jaunt to the sixth annual AFRIMMA Awards in Dallas, where he received the Video of the Year award for his single from earlier this year, “Dumebi.” A week before that, he was on stage at Nigerian music awards ceremony the Headies accepting the award for Next Rated, typically given to the country’s most promising act — so his sensitivity to the mild weather is inevitable. While I grab tickets for us, Rema and another member of his team head into the gift shop, eventually emerging while wiggling his body through a black American Museum of Natural History hoodie to wear under his shearling. He’s also wearing black knit gloves. “It’s freezing, bro,” he explains.

I suggested meeting at the Planetarium because the artwork for Rema’s three EPs so far — Rema, Freestyle EP, and Bad Commando — have featured illustrations of floating objects and UFOs. “I use space to represent how I think out of the box,” he tells me as we begin to explore the area. “Space is also a theoretical understanding of the world. I use it as a type of spirituality, so that people who don’t understand spirituality can have it broken down.”

None of Rema’s music feels ostensibly spiritual. The majority of his songs center around his pursuit of beautiful girls who he can’t resist. Beyond his two most well-known tracks — “Dumebi” and this year’s “Iron Man” — his eponymous debut EP also featured the silky love story “Corny,” and poppy-trap tracks like “Why,” dealing with teenage emotions about a girl who isn’t paying him sufficient attention. On the recent single “Lady,” he coos over an uptempo beat by Altims — an accomplished Nigerian producer and DJ who’s worked with national stars Tiwa Savage, D’Prince, and Korede Bello — that sounds like it could suit any of the rising stars in reggaeton. If there’s something spiritual to be gained from this music, it’s how serene Rema manages to sound regardless of the production he’s engaging with.

“He has melodies he just brings out from nowhere,” exclaims Ozedikus, an in-house producer for Nigerian pop powerhouse Mavin Records who produced both “Dumebi” and “Iron Man.” He started sending beats to Rema after they met last year, but their biggest song together was a happy accident: Ozedikus originally crafted the beat for “Dumebi” for another artist who, while wrapping up a late night session, handed the beat to Rema when they were ready to call it a night. “Rema knows how to bring the best out of every beat. Sometimes, he’ll ask me to leave it halfway done and work on it unfinished. He’s every producer’s dream. He just makes work easy.”

For his part, Rema declares that these talents are a direct reflection of his relationship with a higher power. “Somehow, some way, I feel like I get ideas only because of the Holy Spirit,” he says excitedly. “Everybody have their own spiritual understanding and gift. I have this gift, which is a secret to me, because it works. That’s how strongly I believe in God. It’s not musical.” When I pry about what this secret gift is, Rema bashfully demurs before eventually throwing me a bone: “This is a gift of guidance. You know where you’re going when you see the signs.”

HELMUT LANG jacket + pants

HELMUT LANG jacket + pants

When he was barely a teenager, Rema gained the courage to investigate the booming noises he heard from a building while walking to school in his native Benin City (the capital of Nigeria’s Edo State). As he reached the door, he confirmed that it was a recording studio where boys in his neighborhood would pool enough money for session time. Rema had never recorded music up to that point in his life, but when the studio’s producer asked him what he was looking for, he professed, “I want to rap.”

It was common practice for an artist to come with a readymade beat to rap over; Rema didn’t even have money to pay for one. But the producer was impressed by the gumption contained in his adolescent frame, so he made him one on the spot. The song that resulted was, according to Rema, not very good at all — but the producer told him to come back when he was ready to make more music. “90% of my recording coming up was free — every studio I went to,” he tells me while looking at an imposing display of the solar system suspended above us. “I kept me getting free studio time a secret because if people knew, they’d get upset. ‘Why are you treating him more special?’ I call it grace.”

A year later, Rema was out of the studio and searching for young people at his church who were passionate about rap music. Agreeing that he’d perform for the congregation, Rema ensured free access to the church’s studio whenever he wanted. “It was a blessing,” he says as we walk around. “I was staying all night for recording and auditions.” It’s rare that a church in a Black community — maybe any church, for that matter — would be so openly supportive of rap music, but Rema’s youth minister Pastor Chris took early notice of his ambition. Eventually, Rema became the head of the church’s Rap Nation program, which gave aspiring young artists a platform to nurture their talents in front of fellow worshippers.

“I was actually hyped,” he recalls. “People started popping up, even girls. To be honest, I wasn’t that good — I just felt like I was different. But the more we kept performing, the more people started making their own groups.” Rema’s first project during his tenure in Rap Nation was forming the seven-member 7th Dimension, named after the closest theoretical realm to God. Eventually, Rema and fellow aspiring rapper Alpha P, formed RnA, which won top prize on the local talent-seeking TV show Dream Alive with Pikolo in 2015.

The video for their single “Mercy” from the same year features a short-haired 15-year-old Rema, with mannerisms and vocal delivery more aligned with conventional rap than his current genre-defying approach — his hands moving a mile a minute, a few spirited “huh”’s adding emphasis to his punchlines. But it was the video he uploaded in February of 2018 that would permanently change the course of Rema’s life. Sitting in a car’s driver’s seat, rocking a crimson hooded jacket with his locs hanging just above his brow, he freestyled to Nigerian star D’Prince’s “Gucci Gang,” which also featured homegrown musical icons Davido and Don Jazzy. The 51-second clip went viral in Nigeria and made its way to D’Prince, who eventually reached out to Rema and brought him to Lagos to meet his brother and head of Mavin Records, Don Jazzy.

PYER MOSS pants, jacket, jacket (worn over). UNIQLO shirt. NIKE shoes.

PYER MOSS pants, jacket, jacket (worn over). UNIQLO shirt. NIKE shoes.

In January of this year, venture-building company Kupanda Holdings and private equity firm TPG Growth (the latter previously investing in Spotify, Uber, Airbnb, and Trace Media in Africa) struck a deal with Mavin that allowed for the birth of the label’s Jonzing World imprint. D’Prince brought Rema to the Mavin family as Jonzing’s first artist, and from there he allowed the young star to develop his sound for the better part of a year.

“I remember that day like yesterday — almost like a prophetic scripture from the Holy Bible,” D’Prince recalls while discussing the day he found Rema’s freestyle. “I was very impressed with the way he controlled the freestyle. His ability to flow both on afrobeats and a trap beat is one of the qualities that sets him apart. He has this youthful, fun vibe, and I’m happy he’s serving the world different genres.” Earlier this year, Rema released his self-titled debut EP which included one of 2019’s biggest Nigerian hits: “Dumebi,” a contagious afrobeats number that’s proved a mainstay at parties and on radio stations in West Africa, as well as areas of the U.K. and U.S. where there’s a significant presence of the Nigerian diaspora.

Then there’s “Iron Man,” which takes cues from classical Hindustani music while positioning Rema’s light, nasally harmonies to melt perfectly into the production like another instrument in the mix. The song ended up on former U.S. President Barack Obama’s annual 44-track summer playlist (the only Nigerian artist to appear on it), and since then Rema has released two more four-track EPs, grabbed a few prestigious African music awards, and is poised to become his country’s next superstar — bridging gaps between cultures in a way that many of his most successful predecessors have yet to figure out.

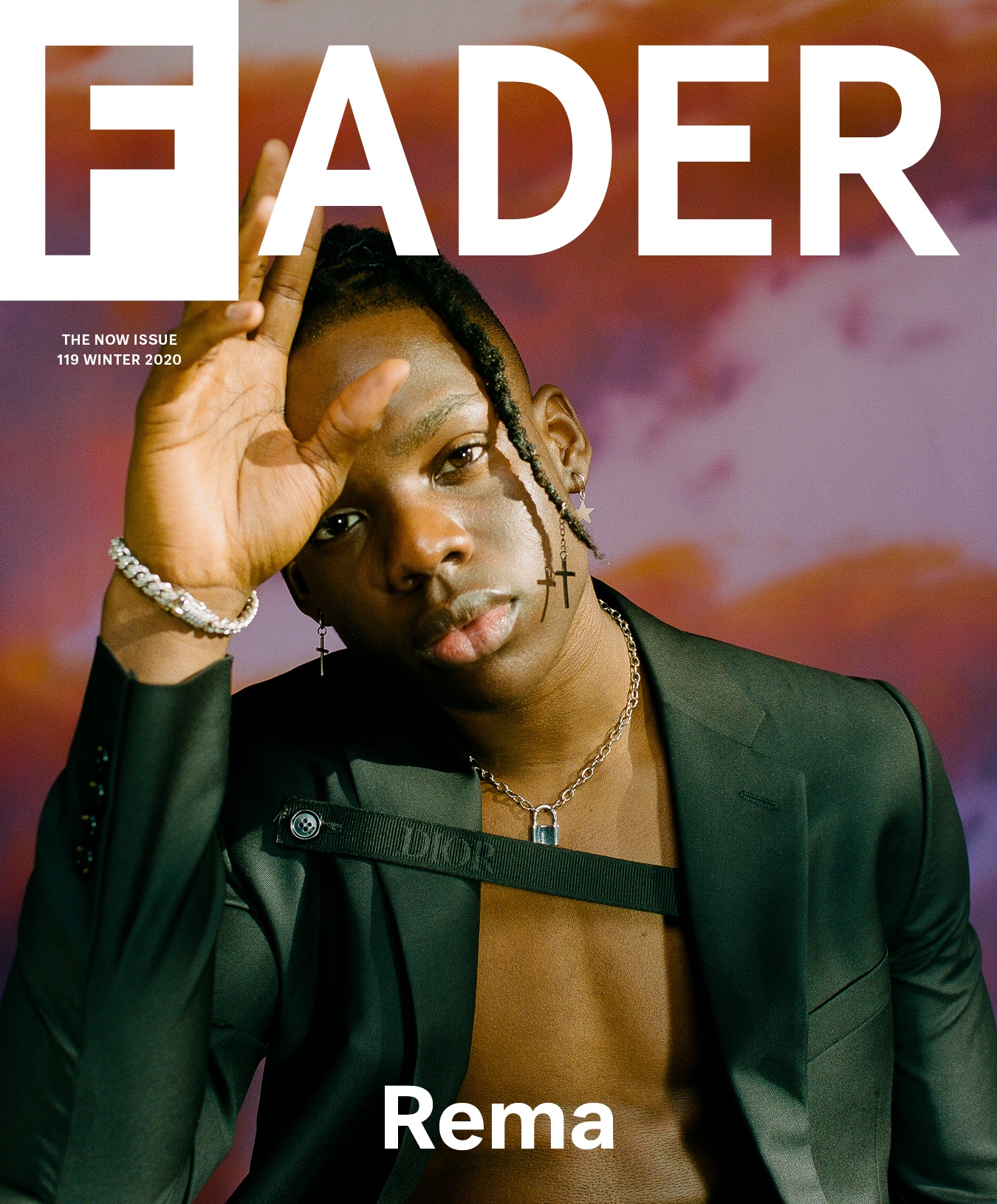

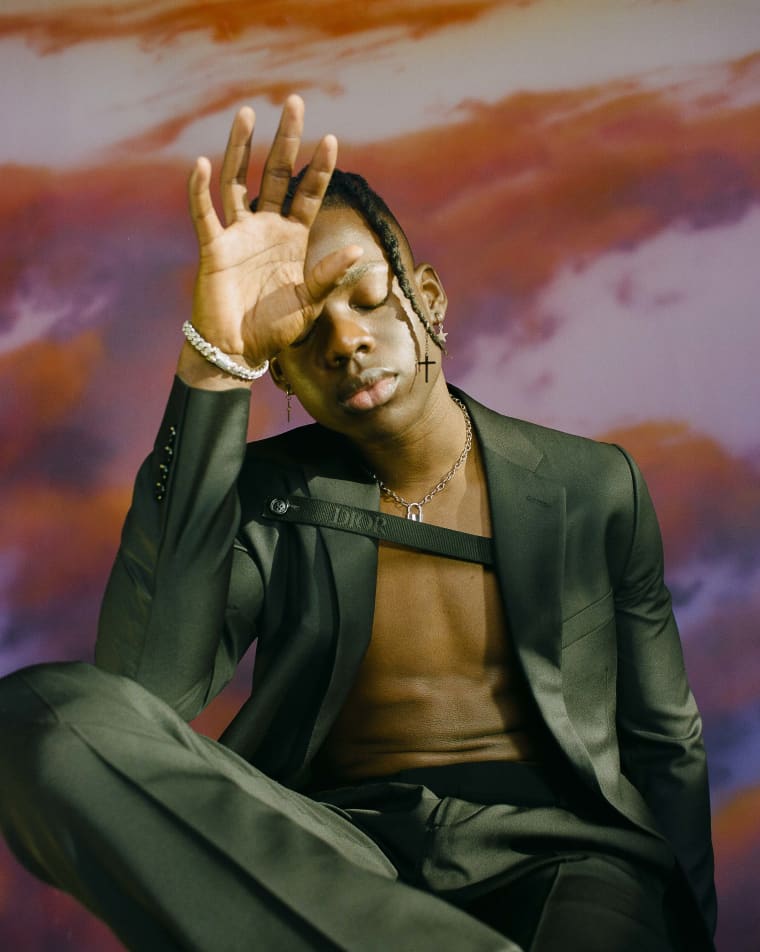

DIOR jacket, pants, shoes. RHUDE vest.

DIOR jacket, pants, shoes. RHUDE vest.

Over the past nine months, Rema has placed himself at the forefront of a new guard coming out of West Africa that’s taking lessons from watching their forebears test the waters of international viability. The three kings of Nigerian music’s current quest for global dominance are Wizkid, Davido, and Burna Boy — all born in the early ‘90s and benefitting from the internet’s early stages of globalization. Wizkid’s autobiographical smash “Ojuelegba” attracted London’s Skepta and Toronto’s Drake for its remix; Davido notched a collaboration with Meek Mill in 2015 and has had singles like “If” and “Fall” enter regular rotation on U.S. urban radio stations, while Burna Boy’s African Giant seamlessly included appearances from Future and YG.

What separates Rema’s generation from these three artists is how it goes about evoking its cultural identity, which is more elusive than the more easily traceable roots of those before them. Looking at Rema’s faded locs, chest bags, and carefree music videos, there isn’t a clear distinction of where he’s from; his point of origin could justifiably be anywhere from Kingston, Cape Town, Berlin, Washington D.C., or Lagos. Regardless of from where they hail, the majority of kids his age — born in the late ‘90s through the early 2000s — are absorbing the same mood board-informed content on the internet and speak a borderless language of aesthetics to one another. That approach spills out into Rema’s music, which feels less anchored by afrobeats than many of his peers. “Music, I don’t plan it — even the beats,” he claims. “Sometimes I get in the studio and hear the producer playing with some keys and I’ll be like, ‘Can I jump on that?' Sometimes, I have so many melodies that the producer gets confused about what to add to the beat.”

Rema isn’t the only young artist with this approach in West Africa right now, but he might be the one who carries the most mainstream promise. Ghana and Nigeria’s alté scene — short for alternative, with focuses on fashion and visual presentation along with music — is producing some of the most exciting work in the region; Odunsi (The Engine) makes afropop-tinged R&B and signed a publishing deal with Warner Music in 2018, while Santi permeates cool with his hushed melodic raps and signed to LVRN earlier this year, the label that counts 6LACK, Summer Walker, and D.R.A.M. in its roster. Ghanaian singer Amaarae is making some of the most lush, emotionally intelligent music in R&B; Lady Donli, from Nigeria’s capital city, joins traditional Nigerian sounds with neo-soul and highlife. This new crop of artists are sonically crossing over before they even have conversations with artists outside of the continent, which is an exciting prospect as we enter a new decade.

“Rema is definitely unique and the first of a kind from Africa — he can fit across nearly every single genre, not just afrobeats,” says Colin Batsa, who’s the Head of Urban UK at Caroline International. Before the release of Bad Commando, Rema signed a distribution deal with Caroline to spread his music beyond Africa’s borders; Batsa says he found out about Rema through a friend who developed an app that tracks the “velocity of African songs on YouTube.” After seeing Rema’s “Gucci Gang” freestyle, he says he got a strong sense that Rema was something special. “He’s leading a new wave of African artists that will take the afrowave sound to a global arena. World music is definitely becoming genre-less.”

At the Hayden Planetarium, Rema and I finish up our time together by walking through the timeline of our solar system, ending up in a room dedicated to different types of rocks at the American Museum of Natural History. He expresses his skepticism of any of the specimens on view being real before we find a bench to sit and talk, both bored by what this particular room has to offer. He tells me about growing up in Benin City, known for its bronze sculptures and dominance in the region between the 13th and 19th centuries; because of how culturally traditional the city is, Rema says that being even slightly different there assures that you’ll stick out like a sore thumb.

Throughout our day together, he exerts much more energy and capacity for conversation than the “shy” narrative that’s been placed onto him in previous media coverage. His giddiness often results in him visibly thinking through what he’s saying — the expected demeanor of a teenager who’s expected to talk about their creativity on a regular basis. He glowingly talks about his father, who died around the time Rema was eight years old. “He was a really good dad — he had a nose ring, he was cool,” he lights up, mentioning that he read a lot as a child because his father was a managing director of a Nigerian company that printed and sold books to local schools.

His dad eventually left the book business to become a member of Nigeria’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP); when breaking down the party and its competition, All Progressives Congress (APC), Rema says that neither holds a level of moral high ground. “The reputation for both parties is that they’re fucking greedy — it’s nothing more,” he says with assured snicker. “Greed is part of everything.” On Bad Commando’s “Rewind,” Rema gives his own assessment of his country’s political climate over warm bass strums and percussive hits: “Government y’all tell me what y’all governise / The people never organise / Even when I try to socialise / The people make me lose my mind / My people suffer, political poker / I put the burden of the masses on my shoulder.”

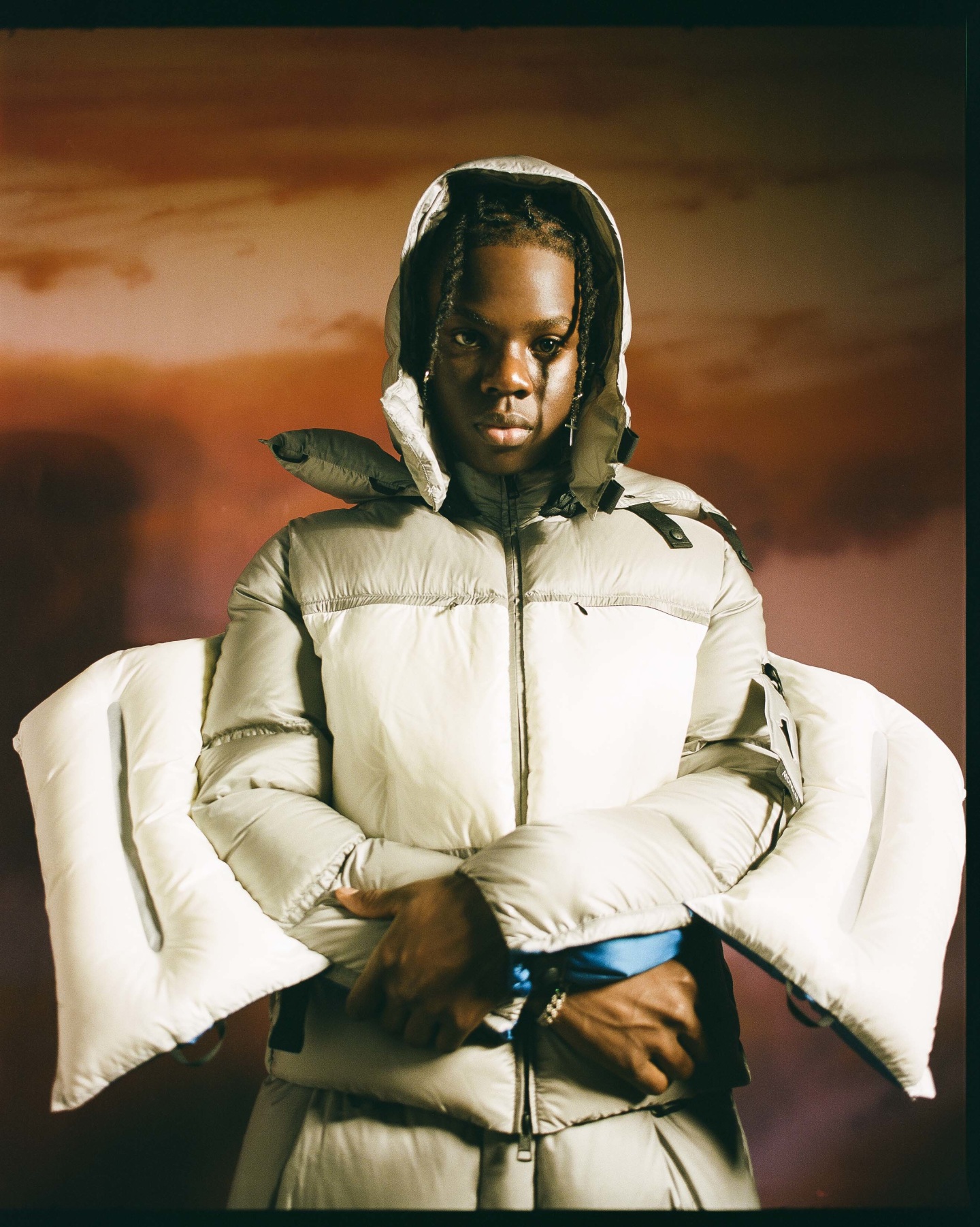

MONCLER GENIUS x CRAIG GREEN jacket + pants.

MONCLER GENIUS x CRAIG GREEN jacket + pants.

Though the song quickly transitions into the type of lovely dance track that the majority of his other work leans towards, “Rewind” frames Rema as someone concerned with how his country is being managed — someone who sees the value in sharing that he’s aware of what’s happening. “When I was writing that song, I wanted to write it for the government — but I stopped halfway,” he admits. “Because of how fast I grew in the music industry, people feel like I don't have to face struggles. I want to actually talk about the government, but I’d rather take it step by step before I go there in full.” Right now, Rema’s main priority is gaining support from the masses by meshing as many sounds as possible; once he feels like he’s comfortable with his base, he says he’d like to start adding more political commentary to his music.

We end our three-hour trip to the museum and hop into an Uber headed for SoHo so Rema can get his real first taste of being out in the New York City streets — though it seems unlikely that he’ll enjoy himself, judging by how easily he gets cold. For the majority of our ride, Rema’s sifting through Instagram, pausing to watch a series of videos from Burna Boy’s sold-out show at Wembley’s SSE Arena the night before. The footage depicts Burna surrounded by phone lights from all angles — remarkably similar to the galaxy displays we’d just seen. Clearly enamored and motivated by what he’s watching, Rema sparks a 15 minute-long Burna Boy appreciation session from everyone in the car; talks of his rise, his reluctance to give up, and him finally realizing his mission are some of the highlights of the exchange.

Before we head into an Urban Outfitters, I ask him about the type of impact he’s trying to make with his own music in the future. “I only put out music when I need to say something,” he says, half engaging with me, half fixated on a dubbed video of a horse trotting in place in a way that resembles the Nigerian Zanku dance while Burna Boy’s “Killin Dem” plays. “My music might convey things about girls and beautiful ladies, but it’s still a statement about how talented you are, how diverse you are, and how far you’re gonna take the industry. I just speak when I feel like it’s time.”