Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

We’re two weeks into 2026 and a new trend has already emerged: 2016. My entire Instagram feed has been overrun with VSCO-filtered photo carousels, Snapchat memories, and archived Instagram posts from the bygone era. (Personally, I’ve opted out of participating because 2016 wasn’t necessarily the best year for me as an angsty teenager, but also, does anyone really need to see high school me with a puppy dog Snapchat filter?)

The resurgence has seen astronomical numbers in a short time. On TikTok, “2016” searches are reportedly up by 452 percent, and nearly 2 million videos have been made using the #2016 hashtag. According to Google Trends, there has been a 4,050-percent spike in searches that coincidentally raise the same question I’ve been asking since the start of the year: Why is everyone posting about 2016 right now?

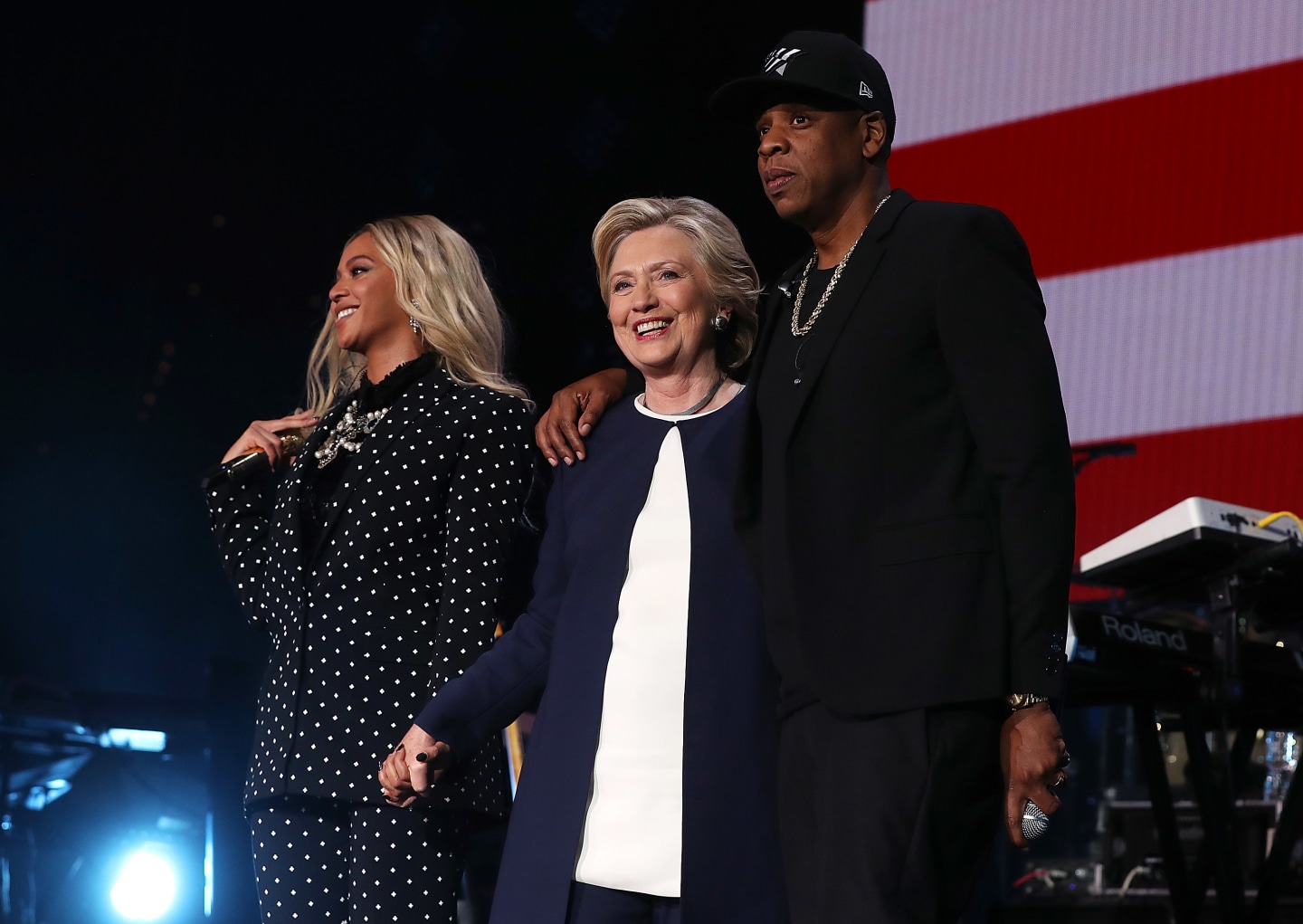

Unequivocally, 2016 was a pivotal year. Pokémon Go and the mannequin challenge were ubiquitous, monoculture trends. The year also saw career-defining releases from many artists turned visionaries: Rihanna’s ANTI, Frank Ocean’s Blonde, Beyoncé’s Lemonade, Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo, and Drake’s Views. Rae Sremmurd and Fetty Wap dominated the charts. Vine was on the cusp of extinction, but pre-fee Snapchat was alive and well, and online personalities like Joanne the Scammer birthed modern-day memes.

2016 had a distinct look, too. Before overly polished microtrends, the fashion world was united in its affinity for logo-emblazoned tees, distressed skinny jeans, plastic chokers, Gucci belts, bomber jackets, and flannels. The downfall of American Apparel paved the way for streetwear giants like Hood By Air, Vetements, Supreme, and Off-White to take its place. Beauty-wise, you couldn’t escape pastel hair, blocky brows, and Kylie Jenner’s lip kits.

Unequivocally, 2016 was a pivotal year.

While 2016 was a cultural touchstone that the rest of the late-2010s arguably failed to live up to, the recaps surfacing on my feed feel oddly selective. Steffi Cao, a Brooklyn-based culture writer, sees the posts about 2016, especially ones made by creators who likely weren’t sentient teens at that time, as “I was born in the wrong generation” nostalgia bait.

Unlike the ’90s and early 2000s, the mid-2010s mark the first era when older Gen Zers were conscious participants. However, some 2016 time capsules don’t accurately nail the exact happenings of that year — i.e., “Neon colors were more 2014 than 2016,” Cao says. But she also doesn’t expect present-day posts to be the most accurate. “Some people were young and were busy learning letters and numbers,” she says. “They will never know the sweet joy of hearing ‘Mo Bamba’ in a disgusting frat house.”

Perhaps the biggest blind spot of the 2016 trend is the political storm that kicked off once Donald Trump was officially elected president in November 2016. The summer of 2016 was the last semblance of normalcy “before everything changed,” says Ruby Thelot, a New York University professor of design and media theory. Thelot vividly remembers a vibe shift after the election. “The day that Trump was elected, on top of personal issues, was like my world collapsed,” he recalls. Since then, Thelot says, the tone of American politics and social cohesion has permanently changed. “It’s as if we entered an era of incessant negative events one after the other — the 2016 election and then, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 — and we have been under duress ever since.”

Even as 2016 signaled a plunge into back-to-back crises and civil unrest, people are still insistent on romanticizing it. To Cao, there has always been a sense of “era nostalgia” on the Internet, but she believes 2016 nostalgia has a lot to do with who is online today. “Right now, Zillennials are a key demographic of posters and consumers on social media, and they aren’t immune to the allure of a better time in their formative childhood years, especially as it marked as the last burst of optimism before larger themes of fascism, disease, and economic uncertainty came crashing down over their adult lives,” she says. “I’m personally always saying the last time I felt truly good about the world was when ‘Closer’ was on the radio.”

“It’s as if we entered an era of incessant negative events one after the other — the 2016 election and then, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 — and we have been under duress ever since.”

Thelot agrees that the impetus behind the 2016 nostalgia is less of an organic revival and more of a commercial one. “When we think about a specific epoch — say, the Renaissance — [the label] describes a unified yet complex moment in time,” he says. But similar to indie sleaze, “people are trying to hodge-podge it and give it a name.” The commodification of 2016 “only serves as selling that time period in retrospect,” he adds, “but not the validity of what actually took place back then.”

And, honestly, who can blame them? 2016 contained the last drops of collective culture before the long-term effects of social media and influencer culture kicked in — before the 2020s rode in, characterized by the distinct lack of culture. So far, the 2020s are drenched in self-awareness and nihilism. Online perception is king, and people are more performative than ever, yet also somehow driven by authenticity, Cao says. Reference and search-optimized phrasing are crucial to digital culture and boosting one’s own visibility online.

“We see this desire to name everything to make it easier for people to reference back to it,” Cao adds. “Tech, in my opinion, is at the heart of what shapes our culture right now.”

In between all the AI slop and rage bait taking over my feed, I won’t lie, it’s been nice to see posts of my friends reminiscing about their past selves in deep-fried, rose-tinted filters, captioned with how they were unaware of what the future would hold — pictures that were originally created and shared at a time when posting yourself online meant something entirely different. At the same time I can’t help but feel the temporality of this band-aid, and wonder if there’s a better use of our time seeking that same optimism in the real world right now, instead.